I want a DDR-like game for Klavarskribo. I woke up with more ideas this morning. I’m just going to spew them out so I don’t forget any of them.

I’ve often complained about common (traditional) notation as like reading “assembly language” for music. It leaves so many intentions of the composer implicit. Yes, certain things can be easily ascertained, like the key of the music (from the key signature) and that a certain passage should be repeated (from the repeat signs). But there are so many other structures and patterns that I wish were explicit in order to save me a lot of time as a learner/performer of the music. In programming, I would never dream of copying and pasting a whole ream of code just because I want the same thing to happen in another context except for one little change in the middle. Yet in music notation, that is the order of the day. As a student of the piece, I have to manually double-check that, yes, everything in this section is exactly the same as that other section, except for this little riff right here. Or perhaps it’s exactly the same, but it’s in a different key. If I were writing software, I would store the current key in a local variable. Then, if I wanted to do exactly the same thing but in a different key, I would just call the same function, initializing the key accordingly. Or I’d compose the function with a “transpose” function. For Pete’s sake, I wouldn’t copy and paste all of my code, and then update all the hard-coded pitches, when they’re all the same fixed interval from a sequence of pitches I’ve written elsewhere. But in music that’s how it’s been done for a thousand years or so (except that “copy and paste” was a bit more painstaking).

So that’s why I liken common notation to assembly language. How does Klavarskribo improve on this? It doesn’t. If anything, things are much worse, i.e. if you take “assembly language” pejoratively. But I’m starting to recognize Klavarskribo as a “better assembly language” for music. If you’re going to leave structures and patterns and intentions implicit, then you might as well go the whole way, and encode the notes in a normalized, clean-slate sort of way. In Klavarskribo, there’s no distinction between G-sharp and A-flat, for example. Likewise, there’s no key signature. Klavarskribo gives you a notation that strips music of its theory.

Why would I want this? Wasn’t I just complaining about all the effort it takes to figure out a piece of music when the composer leaves so many intentions unspecified? I do hate that process of figuring out what shouldn’t have to be figured out and is only that way because the notation doesn’t support it. My attitude when writing a book is that it’s much better for me to put in the extra effort upfront in researching a technology or specifying a behavior, etc. Otherwise, that extra effort will have to be multiplied a thousand-fold, leaving it up to my readers to repeat that work when I could have saved them all the trouble. As an author, I want to save my readers all that trouble and throw them as many bones as I have at my disposal. I don’t blame composers; they’re just using the traditional medium they have. But I do long for musical representations that make more intentions explicit.

That still doesn’t answer why I like Klavarskribo. Correct, Klavarskribo doesn’t help in that arena at all, except perhaps to provide a cleaner slate from which to build. By removing all theory (other than the assumption of a 12-note world), it creates a clean, not-tonally-biased notation. I suppose for atonal music it does help, because it removes lots of misleading hints (accidentals that aren’t really accidentals, etc.).

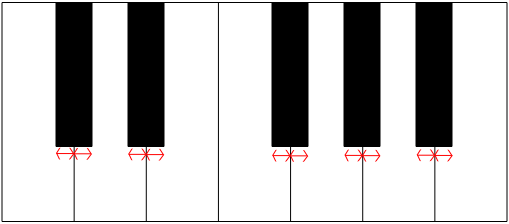

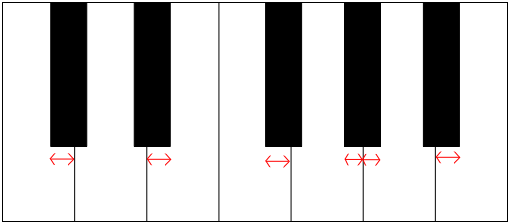

Right now, the reason I like Klavarskribo is its great promise for enabling easier sight-reading. And not just sight-reading, but reading a piece for the first time which I ultimately intend to play from memory. I’ve always been a terrible sight-reader. There are so many variations to digest when sight-reading a piece. I won’t lie. The key signatures do help, especially if there aren’t a lot of accidentals and I’ve been practicing my scales. “Okay, I won’t be playing any of those notes that aren’t in the key of D-flat.” That certainly simplifies things. So I do have some unanswered questions about how Klavarskribo will fare without highlighting accidentals. But I see a lot of potential in totally equalizing the keyboard landscape and removing fear of the black keys for beginners. Heck, you don’t need to know anything about music to start reading Klavarskribo. Common notation is laden with concepts like “keys” and “sharps” and “flats” and “naturals” and “clefs”. I’ve been playing piano since I was six years old, I have a professional music degree, and I still suspect that I will never completely overcome the cognitive overhead of all these potential combinations and variations that are hard-wired into traditional notation.

To me, sight-reading is a different species of musicianship. I watch proficient sight-readers and I’m amazed at how unquestioning they are about what they see. You could throw a bunch of “wrong” notes in the manuscript and they would keep on playing without skipping a beat. Perhaps they’d have some mild bemusement, but they won’t get derailed like I would. There is more of a direct relationship between what they see on the page and what their fingers do on the keyboard. Their ears don’t get in the way, and I mean that in the best way possible. For me, all the notational clutter clogs up that channel. And I suspect that’s true for a lot of people.

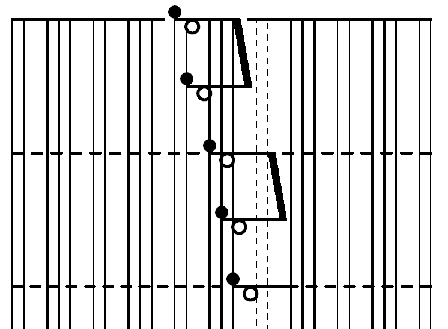

In the computer game I’m envisioning, you would get visual feedback on what you’re doing, just like you do in DDR. In fact, there should be a free-play mode where what keys you play show up instantly in Klavar notation on the screen. That way, you can start with what you’re thinking about musically, e.g. a C-major chord, and then instantly see what it looks like in Klavar. It seems like that way you could start hooking up the neural connections without any effort. Play around and see the notes appear on the screen. “So that’s what Klavar notation looks like.” (With traditional notation, you’d have to first answer all these questions like what clefs to use, what key are we in, is this a G-sharp or A-flat, etc.) Rather than reading music, you’re watching it appear on the screen in response to what you do, and the correspondence between the keys you hit and what you see is quite natural and obvious.

In the play-along mode, you would have the notation scroll up the screen, like a piano roll, and just like the arrows do in DDR. This is where you test your sight-reading ability, getting immediate visual feedback on the screen about how you’re doing, just as you do in DDR with messages like “PERFECT!”, “GOOD!”, etc.

I would also want a silent-play mode where your ears truly have no opportunity to get in the way. You would still know when you hit a wrong note based on the visual feedback, but you won’t get derailed by weird-sounding notes, whether right or wrong.

Heck, I’d maybe even want a random mode, where you can really push the bar on this “mindless”, or rather unconscious, intuitive connection being forged between your eyes and fingers.

Klavarskribo and accompanying learning tools are only one piece of the picture that I envision for refactoring music representation. In software engineering, refactoring means “improving the design of existing code”–without changing its behavior. To me, refactoring a piece of music would mean changing the representation–or adding multiple representations, while leaving the content unchanged. All for the purpose of making the piece easier to comprehend, and at multiple levels. More on that later…