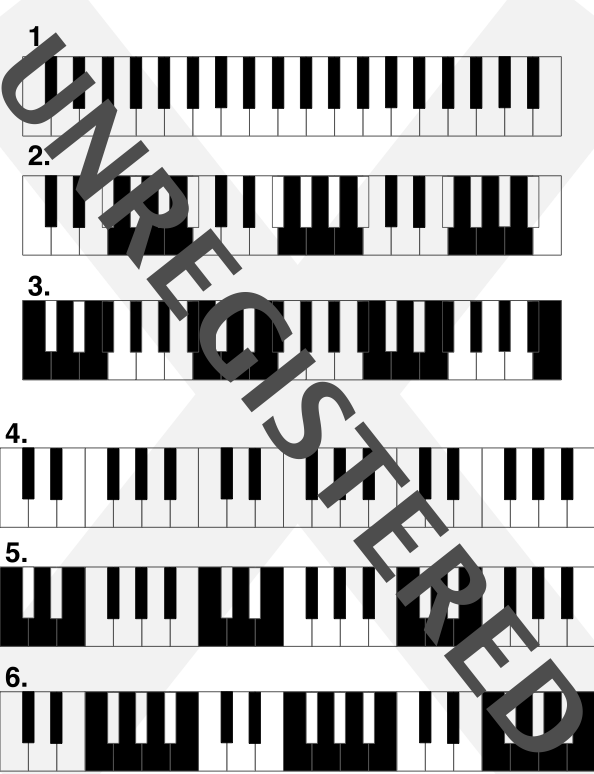

A few weeks ago, I was sitting at the piano and contemplating what I had been learning about the Janko keyboard. I was thinking about all the different scale patterns on the traditional piano keyboard and how different they are. There are 12 of them. (I would tend not to count the minor key scales separately, since they’re essentially just offsets from the major scale, as are the other modes.) Johannes Drinda introduced the Janko keyboard to me and in that same email wrote:

The advantage of the uniform Janko keyboard pattern is mind-boggling:

The Janko keyboard pattern does away with practicing scales, would you believe?! This is the true reason, why so many hobby musicians (like me!) got stuck with playing mostly in C-major & A-minor scales and lost out on a great deal of musical joys and creativity.

With Janko one only needs to learn one major and one minor scale-pattern. From then on one can play all 24 major & minor scales.

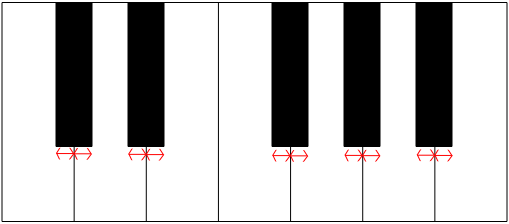

As I sat at the piano considering these words, I realized that there are really twice as many scales as that, if you count both hands separately. My left hand is not a copy of my right hand. It’s a mirror image of it. The muscle movements and fingering for playing D-flat major in my right hand are much different than the movements and fingering for playing it in my left hand. So then there are actually 24 different scale patterns to learn (12 for the left hand, and 12 for the right hand), or if you count major and minor scales separately (as Johannes did in his email above), then there are 48 separate scales to learn (24 for the left hand, and 24 for the right hand).

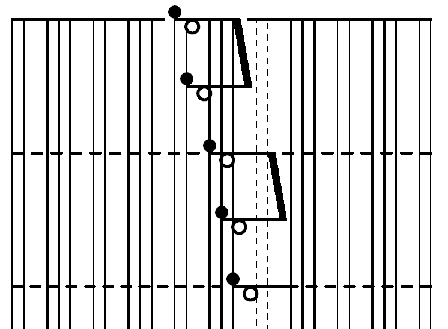

The fact that one hand mirrors the other also reminded me of Vincent Persichetti‘s “Mirror Etudes”, a selection of which I played in my junior or senior recital in college (I can’t remember which). One thing I liked about this piece is that all I really had to do was learn the right hand, and then make the same movements in my left hand, taking advantage of the fact that the piano keyboard mirrors itself (pivoting around D and A-flat). Persichetti used this algorithmic device (where one hand’s part is a simple function of the other hand’s part) to very nice effect, perhaps in some ways in spite of the device.

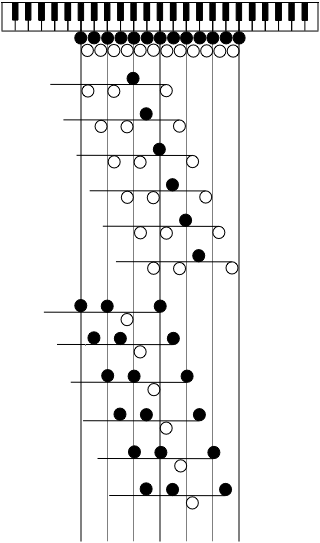

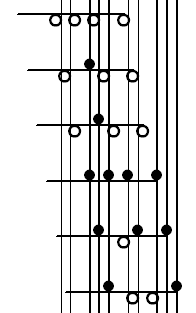

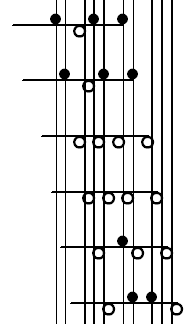

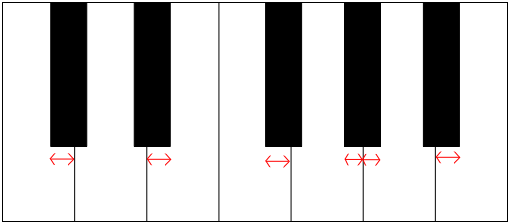

The next thought I had was: “What if each hand had its own keyboard, so that the same movements and fingerings would produce the same notes?” If I traverse the five-finger position from my thumb to my pinky in my right hand, then the pitches go up (get higher). On a regular piano, if I do the same thing in my left hand, they go lower. That’s the mismatch. What if they both went higher, so that playing a given part in the right hand felt exactly like playing that part in the left hand? I then supposed that this would require two different keyboards: one for my left hand and one for my right hand. The right-hand keyboard could be the “normal” one, and the left-hand keyboard would be reversed: moving to the left causes the pitches to rise, and moving to the right causes them to descend. We could then speak, instead of moving left or right, of moving outward or away from the body (ascending in pitch), and inward or toward the body (descending in pitch). With a setup like this, if you act as if you’re playing the Persichetti etudes on a traditional keyboard, you’d now actually be playing both hands in unison (robbing the piece of its character, but that’s not the point).

Google can have a tendency to quash creative thinking. What seems like an original idea turns out to be not so original. Then again, it can also have a validating effect. Regardless, someone has already had this idea (and patented it). There’s also a diagram showing how the left-hand keyboard is re-mapped. Actually, now that I look at the diagram, I see that it’s not quite the same as what I had in mind. I was thinking of just reversing a traditional piano keyboard. The diagram for this patent shows a 6-6 pattern (like Janko) for both keyboards. So in that case I suppose you could truly say that the user would only need to learn 1 single diatonic scale pattern, as opposed to 24. Not bad.

But that’s not all. A pianist named Christopher Seed has actually built a left-handed piano. (Be sure to check out his videos page too, where he shows off his ambidexterity.) Not only that, but his website offers a simple hardware module called The Keyboard Mirror that transforms a MIDI keyboard into a left-handed (reversed) MIDI keyboard! This probably wouldn’t be too difficult to implement in software too. So to try my idea out, all I’d need is two MIDI keyboards, one unmodified and one with the Keyboard Mirror plugged into it. To keep things really interesting, I could try switching them around: not only right/normal, left/reversed; but also left/normal, right/reversed.

I just had a funny thought: playing Persichetti’s Mirror Etudes on a left-handed piano would be almost exactly like playing them on a traditional piano! (Except that when you try to voice the upper parts, you’d start wondering why the bass part is getting louder!)

Now, for a real mind-bending exercise, try playing the Mirror Etudes using a left-handed (reversed) keyboard for the left hand and a traditional (not reversed) keyboard for the right hand. Of course, that seems about as sensible as using Vim with a Dvorak keyboard.

Update: When I wrote that last paragraph earlier tonight, I hadn’t realized that playing the actual Mirror Etudes using symmetrical manuals would be “as if” you were playing both hands in unison on a traditional keyboard. The simplicity of this two-way function (reverseHalf mirrored = unison; reverseHalf unison = mirrored) obviously hasn’t sunken in yet, since it’s still all just up in my head. Yes, I’ve gotta try this out!